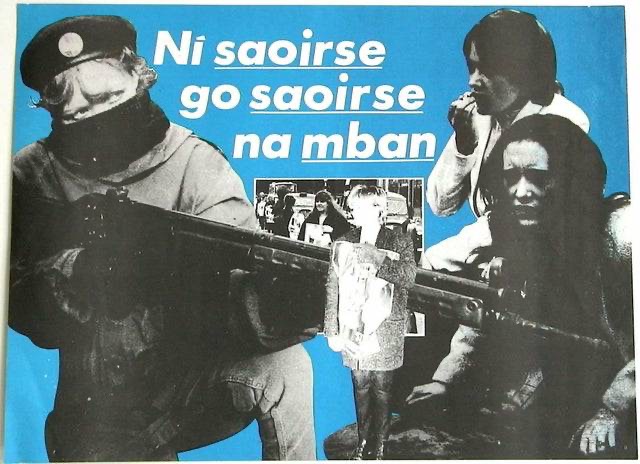

This short pamphlet, originally published as part of an internal Sinn Féin education series called Republican Lectures in 1984, is an excellent explanation of the basis of women’s oppression in Ireland and the relationship between the Women’s and Republican Movements from a Socialist Republican perspective.

WOMEN IN IRELAND

REPUBLICAN LECTURE SERIES NO.8

1984

THIS LECTURE is about women in Irish history and the role of the Republican Movement, past, present and future, in the struggle for women’s liberation.

More than 60 years ago, Constance Markievicz spoke about the three great movements in Ireland at that time: the national movement, the labour movement and the women’s movement. All three converged in 1916 in one fateful attempt to achieve the dominant goal – national freedom. Afterwards, they were to drift apart on separate roads, occasionally crossing but never uniting. In fact, the women’s movement was largely dormant until decades later.

In recent years republicans have begun to reach a concrete understanding of the vital necessity of uniting the labour movement with the national movement once again, not just as a subservient ‘labour must wait’ part in order to mould the struggle against foreign occupation with the struggle of workers against social and economic repression. The Republican Movement has accepted the need for this new direction and the necessity of re-analysing our attitudes in that area.

When Cumann na mBan was founded in 1913 it quickly became the dominant women’s movement, concentrating all of its energies more and more on the expected rising. Many suffragettes joined its ranks, others were disappointed that it was not emphasising women’s rights. Inghidhe na hEireann(Daughters of Ireland), led by Helena Molony and Maude Gonne, merged with Cumann na mBan but always kept an identity within it as a feminist grouping.

The heroism of the women of Cumann na mBan in 1916, later on the prisoners issue and through the Tan War and afterwards is indisputable. However, their role was not the same as an IRA Volunteer’s role. Cumann na mBan concentrated on duties such as scouting, dispatch carrying, intelligence work and first-aid. It has remained a separate body until today. The role of Cumann na mBan was a vital one, but Markievicz herself criticised the role as being primarily a back-up one, and it was in the ranks of the Irish Citizen Army that she fought in Stephen’s Green in 1916.

DETERMINATION

There are many women today, however, fighting in the ranks of the IRA and Cumann na mBan side-by-side with male comrades. And fighting does not only mean shooting at the enemy, bombing economic and military targets and so on. In Armagh Jail republican women prisoners are at the same height of resistance and depths of degradation and suffering as the male prisoners in the H-Blocks. However, it is also true that the number of leading posts held today by women (and this applies also to Sinn Féin), does not yet reflect the number of women in the movement, their abilities, and their revolutionary determination and enthusiasm.

It is interesting to consider that many young women took part in the IRA’s bombing campaign of Britain in the ‘30s. They carried out bombing missions as IRA Volunteers, with no difference in role to their male counterparts. A number of them were captured and served long prison sentences, alone in several cases, in English prisons. These women are still with us today and we know them as possessing the same qualities of determination, dedication and intelligence which enabled them, then, to invade the male preserve. Nevertheless, none emerged in leading roles in the IRA following the campaign – this was definitely the preserve of the men who were active in the ’30s alongside them.

Because of the indoctrination of all of us, the idea of ‘grey-haired old ladies’ or ‘middle aged mothers’ as leaders of our revolutionary army appears incongruous. Yet the case of ‘white-haired old gentlemen’ in the same role has almost been a point of honour over the years.

Why do so many speakers refer to the ‘girls’ in Armagh rather than ‘women’? Is it because girls can be allowed the wild impetuosity of becoming involved in military struggle whilst once they are women they must settle back into their appointed roles as wives, mothers and other, more subservient auxiliary roles which are dictated by the characteristic fashions of the male dominated society?

We must remember that in so many revolutions throughout this century, women have plated, and have been encouraged to play, an equal role in the fighting, but once that fight has been won they have been expected to return to their previous oppressed role. The fairly recent example of Iran is one of the most glaring examples. Perhaps some would differentiate that there the force of Muslim thought makes women’s repression inevitable. We should remember therefore that here in Ireland we have an equivalently extreme view of women, making women here certainly the most oppressed in the so-called developed countries.

Before we go on to discuss the major areas of women’s oppression in Ireland it is necessary first to understand that this oppression – although in the mould of worldwide oppression of women – has its own definite colour and roots in the development of Irish social and economic and national history. In view of this, it is vital to understand the events which have placed Irish women in their present position. To do this we should go back to the earliest records on the subject.

BREHON LAWS

By the end of the 7th century early Irish society had evolved a system enshrined in the Brehon Laws where there were, in theory, a considerable amount of rights accorded to women. In practice, the reality may have been near total male dominance but these laws are still a vital reflection of the aims of prevailing thought at the time.

At that time women in marriage kept rights to their own property bought into marriage, men could not make contracts affecting that. Women could only inherit from their fathers if there were no sons, and then could only inherit a life interest in his property which after her death, revered to her father’s nearest male relative. Her family, in such a case, retained a protective interest even when she was married – and this attitude was reflected throughout the society. A wife had considerable protection physically, being allowed to claim back her dowry and compensation if ill-treated or beaten or even slandered by her husband. There were also grounds for divorce, as were madness or incurable illness of her husband, or his loss of his property or refusal to maintain her, or his being sexually unsatisfactory. Divorce was also available by mutual consent. Even where no marriage contract was involved in a relationship, women were protected by law and illegitimacy was almost a non-existent concept. The early Irish church, of course, opposed all this but the Irish insisted on keeping their civil laws separate from church law and the system existed well into the 12th century.

When people speak today of alien concepts being foisted on Irish women they could well look back to this period before the Anglo-Norman invasion and before the latter imposition of English law in the early 17th century.

With the Anglo-Norman invasion of 1169 came the influence of English Common Law. Under this, a woman’s property passed wholly to her husband on marriage and her ability to inherit from him was restricted. The concept of illegitimacy was also introduced, with only children born into wedlock able to inherit. Divorce was excluded. Women would not inherit totally from their fathers only if there was no male heirs.

These new laws exposed women to great exploitation; women’s property passing to their husbands made marriage a business proposition.

SOCIETY’S ATTITUDE

A woman was often forced by her family into marriage. Her total dependence on her husband left her open to physical abuse. Society’s attitude to childless wives and widows altered drastically because of the inheritance laws as did their attitudes to illegitimate children and their mothers.

The Church now insisted successfully that matrimonial matters all now be dealt with in ecclesiastical courts. However, it was common for wealthy men to gain annulments in these courts by false evidence and procured witnesses – shades of present-day hypocrisy in the Church’s attitude to marriage annulments.

All this time of course, women were totally without formal political rights, although strong-minded women could be influential. This position continued under the conquest and plantation of the 16th and 17th centuries. However, although women were subject to men in a totally domestic role, among the lower orders the domestic role often meant a domestic industry also, such as spinning. Labour-intensive tilling, sowing and reaping in agriculture also made women economically very necessary and this afforded some independence. Nevertheless, it is interesting to see in this period the dominant poetic theme of the sad passive women of the ‘Aisling’ poetry always awaiting male deliverance. It reflected society’s view of the proper order.

As time went on, middle class and then poor girls began to receive education. This vitally important work was almost exclusively performed by nuns and there is no doubt that the founders of the religious orders were women of magnificent drive and initiative who by these means increased the expectations of women.

By the end of the 18th century, women like Mary Ann McCracken were involved in revolutionary and radical politics, as they were later in the Young Ireland movement.

The famine of the mid-19th century changed women’s role again. Domestic industries such as spinning were smashed and only in the North-East were women diverted into the factories of the linen industry. The change from tillage to livestock made agriculture much less labour intensive, apart from in dairying, so that women became economically less useful and therefore less independent. Domestic service was the only major employment outside of the North-East. By 1926 60% of women employed outside agriculture in the Free State were engaged in domestic service as opposed to approximately 30% in 1841.

The loss of a woman’s independent economic usefulness meant the loss of independence for a couple wishing to get married – the woman solely performing domestic cooking and housework was unable to contribute financially. This meant that many young people could not afford to marry. It also meant that a woman’s dowry, representing her sole contribution, was of great importance. Two daughters on the marriage market was often unviable for a family so only one would be married off thus hopefully increasing the family’s wealth. Choice of a spouse was also severely affected by this. The marriage rate fell drastically.

DOMINATION

In addition, the increased age at death over the years meant sons were awaiting their parents deaths in order to inherit. They therefore married at a much older age and when they did, married much younger women thus adding age domination to male domination of wives.

Society at the time was dominated by farming community and consequently dominated by these problems, arising unconsciously from economic necessity. The long wait of sons for marriage and the number of unmarried daughters meant sex itself became a major problem. Thoughts of marriage, temptations of the flesh and matters of this kind had to be kept out of their minds and distance had to be put between the sexes. Sex became an obsession in society equated with sin.

At this time, the mid-19th century, the Catholic Church was growing in strength and the number of clergy was growing rapidly. Maynooth was in fact founded in 1795 by grant from the British government to deflect Catholic national feeling and the grant was increased by Peel in 1847. Indeed, in return for grants, Maynooth Catholic bishops accepted the Act of Union and the right of the British government to confirm Papal elections of bishops and the appointment of parish priests. These clergy were mainly drawn from the solid farming families and as a result possessed the values of the faming society which they then spread to urban areas. These attitudes were not confined to the Catholic Church alone; the Protestant Church and the English rulers reflected the Victorian morality of the over-powering prudery – a concept foreign to Irish culture until then – and this spread through Irish society.

The moral values of the Church were also spread by the takeover of the educational system by these clerics. Before the Famine, school-masters often were an alternative authority to the clergy in the community; now church-dominated teacher-training colleges turned out indoctrinated teachers. It was ironic that as educational opportunities for women rose so too did the attitudes of accepting male dominance by their teachers. Nuns, once pioneers in social and educational change, now became the epitome of the prevailing male image of women – obedience and docility. Ireland by the 20th century had the highest proportion of unmarried women over the age of 45 in Europe – one third of the population as opposed to one sixth before the Famine. Moreover, half the emigrating population were women as opposed to one third for the rest of Europe.

GROWING CONSCIOUSNESS

Throughout the 19th century a growing consciousness of women’s rights had led to a demand for participation in government as well as for the organisation of women’s trade unions. Since the Famine, women had to set up and run schools and hospitals. Encouraged by Michael Davitt, Fanny and Anna Parnell had set up the Ladies Land League in 1881 whilst their brother was in jail. This was dissolved when Parnell got out, as women were too radical and militant. In 1876 the Irish Suffrage Society was set up and 20 years later women gained the right to be elected Poor Law Guardians and some local councillors.

It was highly-educated women who were making their names in non-political society at the time and some of those became involved in the women’s struggle and then the labour and national struggle – the historian Alice Stoprford-Green and Mary Hayden, Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington who had a university honours degree and Agnes O’Farrelly (later a founder of Cumann na mBan) was a professor of Irish poetry. It was only when Connolly spoke at a Women’s Franchise meeting in Phoenix Park in 1912 that Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington said that she began to realise that it was votes for women they were looking for and not votes for ladies. Connolly marked the coming together of the women’s movement with the labour movement as he did the coming together of that with the national movement. His chapter entitled ‘Women’ in The Reconquest of Ireland should be essential reading for us all.

He said:

“In Ireland the women’s cause is felt by all labour men and women as their cause, the labour cause has no more earnest and wholehearted supporters than militant women…In Ireland, the soul of womanhood has been trained for centuries to surrender its rights and as a consequence the race has lost its chief capacity to withstand assaults from without and demoralisation from within. Those who preached for Irish womankind’s fidelity to duty as the only ideal to be striven after were, consciously or unconsciously, fashioning a slave mentality which the Irish mothers had perforce to transmit to the Irish child.”

Women had become increasingly militant in their demands, coming into conflict with the Redmondites because of their refusal to support women’s suffrage or include it in the Home Rule Bill. This refusal led to a joint protest meeting of the suffragettes, feminists, trade unions and Sinn Féin.

Women began to receive prison sentences for their protests – which included the throwing of a hatchet at the English Prime Minister Asquith on a visit to Dublin in 1912. The same year, Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington went on hunger-strike in Mountjoy Jail – the suffragettes being the first Irish political group to use this tactic.

The 1913 strike/lock-out brought the women’s and labour movements closer together. Delia Larkin and Helena Moloney had already formed an Irish Women Workers’ Union. Louie Bennett, from a middle-class onlooker of the lock-out, became deeply involved in the labour movement.

UNITY IN STRUGGLE

As we have seen, Cumann na mBan then became the dominant movement, diverting major enemies of women into the national movement. But even those who disagreed with the 1916 Rising were drawn into the national struggle as Cumann na mBan, campaigning for the prisoners, brought suffragettes like Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington onto their platforms. Perhaps a parallel with those of today’s feminists who are becoming closely concerned with the Armagh women prisoners’ campaign and therefore the wider national issue.

In 1917 Helena Moloney, Countess Markievicz, Mrs Gurnell, Kathleen Lynn and Rosy Hackett, all of whom were involved in the Easter Rising, joined with Louie Bennett and Helen Chevenix to successfully pursue two important strikes in the women’s industries.

But the Treaty broke up all this unity in struggle as it did every other progressive development. It is interesting that in the Treaty debates all six women members of the First Dáilvoted for the republican side. It is also interesting to note that five of those sixe were relatives of those who died in 1916 or the Tan War – Mrs Pearse, Mrs Clarke, Mary MacSwiney, Mrs O’Callaghan and Ada English – with only Constance Markievicz elected from her own accord.

Thus republican women effectively lost their voice and this was a contributory factor to the complete absence of any women’s politics from the Treaty until more recent days. This trend has continued in Irish politics – women being elected on the name of dead husbands. Incidently, Garret FitzGerald’s mother was an Ulster Protestant who became republican and fought in the GPO. She brought Desmond FitzGerald into politics, he took the Treaty side, she violently disapproved and she bowed out of politics in protest.

In the Free State, women have made some major progress in the trade union movement, with the increase of women members. They have also been responsible for the widening of trade union demands and the Irish Women Workers’ Union broke major ground in obtaining improved working conditions and safety, the gaining of two weeks holiday as a ‘norm’ throughout industry and full health and hospital insurance – all these gains made by women workers for male and female workers alike.

But in the area of specific women’s rights they have not made such progress, often being confused and divided over the years on such matters as, for example, the employment of married women.

FREE STATE LAWS

The 1937 Free State constitution of de Valera typifies the attitude of society to women and accepted, unfortunately, by many women.

The constitution insists that “by her life in the home, the woman gives to the State a support without which the common good cannot be achieved” and that “the State shall endeavour to ensure that mothers shall not be obliged by economic necessity to engage in labour to the neglect of their duties in the home.” The economic part has been cynically ignored – mothers receiving pitiful children’s allowance and so on – but the overall concept of the woman’s place being firmly in the home and the absence of any male duty there is one that is constantly rammed down women’s throats by a panoply of anti-women legislation and the overall thrust of male-dominated thought and social standards.

Laws such as those governing contraception, the ban on literature on that subject, the prohibition on divorce contained in the 1937 constitution, those parts of the Factories Act controlling women’s hours, the laws governing women’s control of home and property in marriage, the criminal conversation laws which treat women as mere chattels of their husbands, the weak laws supposed to enforce equal pay – but so easy to find loopholes – the laws governing rape inside and outside marriage, the position of women’s entitlement to social welfare payments, discrimination in regard to obtaining loans and grants, the continued denial of legal aid in separation cases, the absence of childcare facilities, and so on, represent the massive blockade that legislation puts up to women achieving an equal place in society.

In addition to this, we also have the attitudes of stereotyping children into definite roles according to sex which continue in the home, through education differences both in subjects taught and in opportunities, the presentation of women in advertising and in the media and violence towards women.

CAPITALIST OPPRESSION

All this mountain of oppression crushes women in Ireland – although in some regards women in the 6 counties would have an advantage over their sisters in the 26 counties. But women in the 6 counties have to face a further burden not only in the brutality of forces of military oppression both in their homes, on the streets, in barracks and in prisons. They also have the weight of coping with thousands of families stripped of the husband and father – thrown into jail, a burden which can only be thrown off with the forced withdrawal of Britain from our country. And the part that women have plated in that fight cannot ever be honoured enough.

What if the Maguire sisters, Anne Petticrew, Vivienne Fitzsimmons, Anne Parker, Ethel Lynch, Pauline Kane, Maire Drumm, Laura Crawford, Rosemary Bleakley and the brave women in Armagh had accepted the role accorded them by this capitalist, imperialist-dominated society?

But in other areas we cannot wait for the end of British rule, nor can we merely make promises about the thing we will do in the new Ireland. We must work as we must on other social and economic issues, in hammering at the oppression of women now.

It is only when this movement recognises the oppression of women, and sees clearly where it comes from – the social and economic results of imperialism – that the selflessness, the dedication and the ultimate sacrifice paid by our women Volunteers in Óglaigh na hÉireann and Cumann na mBan, by the tireless women workers in Sinn Féin and Cumann Cabrach, will be truly recognised.