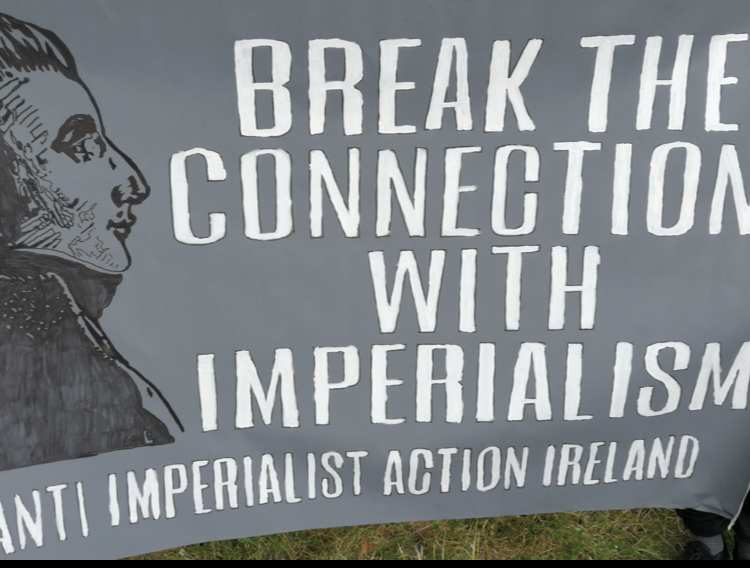

Wolfe Tone was executed in 1798 for the heroic and ground-breaking role he played in the struggle for Irish freedom. He may perhaps appear a remote character, irrelevant to the Ireland of today, but in fact his vision burns bright with relevance and clarity, and those who wish to see a free and united Ireland would do well to heed his words.

In particular those who believe that Provisional Sinn Féin can offer any way out of the current crisis should learn from Tone’s teachings and place their faith, not with traitorous sell-outs, but with the popular movement for liberation. This latest gang of pro-imperialists and reformists, a kind most familiar to the pages of Ireland’s history, disregard every one of Tone’s political beliefs while claiming to be the inheritor of his struggle. Yet still they darken his graveside at Bodenstown. Ever-relevant, James Connolly had the following to say in opposition to constitutional nationalists claiming the legacy of Wolfe Tone:

‘Wolfe Tone and his comrades were overwhelmed by the treachery of their own countrymen more than by the force of the foreign enemy. He was crucified in life, now he is idolised in death, and the men who push forward most arrogantly to burn incense at the altar of his fame are drawn from the very class who, were he alive today, would hasten to repudiate him as a dangerous malcontent. False as they are to every one of the great principles to which our hero consecrated his life, they cannot hope to deceive the popular instinct, and their presence at the ’98 commemorations will only bring into greater relief the depth to which they have sunk. Our Home Rule leaders will find that the glory of Wolfe Tone’s memory will serve, not to cover, but to accentuate the darkness of their shame.’

Likewise Sinn Féin, who would no doubt call Wolfe Tone a “dissident” and “traitor” if he were alive today, pretend to uphold him. It would be worthwhile examining some of his “dissident” views (though they might more accurately be called republican views).

Tone understood well how such traitors to the nation prop up imperialist domination and oppression, and his words speak directly to the role Sinn Féin has played over the last few decades:

‘by disdaining to occupy the station they might have held among the People, and which the People would have been glad to see them fill; they left a vacancy to be seized by those who had more courage, more sense, and more honesty; and not only so, but by this base and interested desertion they furnished their enemies with every argument of justice, policy, and interest, to enforce the system of confiscation.’

Their direct collaboration in the criminalisation of republicanism, a long-standing policy of Britain used to justify the murders of Wolfe Tone and Bobby Sands alike, demonstrates how they ideologically and politically aid the enemies of the nation in their repression of our cause. And not to mention their active support for the ongoing occupation.

Perhaps the most egregious of Sinn Féin’s betrayals is their acceptance of a ‘British community’ in Ireland, that there exists a section of the Irish people who are in fact British, thereby accepting the legitimacy of the imperialist invention “Northern Ireland” as a democratic unit of self-determination. Tone’s most emphatic belief, speaking as a middle-class Protestant, was that history had formed one indivisible Irish nation, that the Protestants striving for freedom from direct English rule (which found expression in 1782 in Grattan’s Parliament) needed to unite with the masses of Catholics, and Presbyterians, in order to actually break from England’s vampire grip. Likewise the Catholics had to recognise that those who had come as settlers in the 1600s were now an historically formed part of the Irish nation. This was a radical idea in Tone’s day but it became widely accepted by the early 1900s – then, in order to justify partitioning the Irish nation, the British imperialists resurrected this zombie. Later Provisional Sinn Féin added their voice to the reactionary and false idea, initially drummed up by the Tories, of ‘two nations’. Wolfe Tone sought to convince all religious communities in Ireland that they:

‘had but one common interest and one common enemy; that the depression and slavery of Ireland was produced and perpetuated by the divisions existing between them, and that, consequently, to assert the independence of their country, and their own individual liberties, it was necessary to forget all former feuds, to consolidate the entire strength of the whole nation, and to form for the future but one people.’

Those who push the line of needing to balance and placate sectarian differences within the confines of Britain’s artificial north-eastern statelet must therefore reject the beliefs of Tone. We must strive to unite the entire Irish people, Catholic and Protestant, on the basis of an independent, united Irish Republic, not kowtow to reactionaries who endeavour to undermine Ireland’s right to self-determination. Separation from England is of benefit to all the people of Ireland and again we are back to Tone in having to assert this reality. As he testified before his execution:

‘From my earliest youth I have regarded the connection between Ireland and Great Britain as the curse of the Irish nation, and felt convinced that, while it lasted, this country could never be free nor happy.’

Reformists who spend their time looking for scraps from Britain and spreading the lie that the imperialists have today become generous and are willing to give up their occupation for a vote would do well to heed Tone’s advice on this question:

‘It is the spirit of Ireland, not the generosity of England, to which we owe our rights and liberties. And the same spirit that obtained, will continue to defend them.’

England will not, after nine centuries, give us back our country because we ask for it nicely. In 1798 Tone wrote:

‘Why does England so pertinaciously resist our independence? Is it for love of us – is it because she thinks we are better as we are? That single argument, if it stood alone, should determine every honest Irishman.’

By this criteria many an Irishman has determined himself dishonest. We are told by traitorous elements of our nation that England would only love to leave Ireland, only that she doesn’t want to provoke a civil war, only that she is so concerned for the Irish people that she cannot lift her motherly hand from us, unless it is “democratically” decided to do so.

Are we better as we are, under the domination of imperialism, or are we better ourselves alone?

Wolfe Tone gave us the answer to this question over two hundred years ago yet still there are thinking Irishmen and women who puzzle over it. They would do well to go back to Tone, to study his words, and to apply them well. The imperialists’ interests lie in the continued subjugation and oppression of Ireland, exploiting our labour, resources and markets for their profits. Those who believe the ruling class of Britain are today of a nicer breed, motivated by democracy and national rights rather than profit and power, are the utopians, while those who stand with Wolfe Tone are realists, the practical section of the Irish nation. As Pearse wrote in 1915:

‘if we to-day are fighting for something either greater than or less than the thing our fathers fought for, either our fathers did not fight for freedom at all, or we are not fighting for freedom. If I do not hold the faith of Tone, and if Tone was not a heretic, then I am. If Tone said ‘BREAK the connection with England,’ and I say ‘MAINTAIN the connection with England,’ I may be preaching a saner (as I am certainly preaching a safer) gospel than his, but I am obviously not preaching the same gospel.’

For the “saner” among us who believe the time for revolutionary politics has passed, recall that it seemed much the same to the Irish people in the 1700s. But the French Revolution of 1789, particularly from 1791 as more radical politics came to the fore, shook Ireland to its core. Tone saw how ‘the unparalleled events, which were going on in France, roused the people from their lethargy’, how it ‘changed in an instant the politics of Ireland.’ The people will be inspired to rise up for progress, to break the chains that bind us, and all those who now claim the days of revolution are past will be scrambling to say they always believed in the revolution. In carrying out the coming revolution, we cannot forget the thought of Wolfe Tone, a guiding light for the Irish revolution.

Tone’s vision has far from yet to be attained. What he died for is yet outstanding. For any Irish revolution to come together successfully it must break the connection with imperialism and aim to unite the Irish people, regardless of religious persuasion, in the pursuit of the Irish Republic. What Pearse said in this regard in his 1913 Bodenstown speech is as true then as now:

‘let us make no mistake as to what Tone sought to do, what it remains for us to do. We need not re-state our programme; Tone has stated it for us:

‘To subvert the tyranny of execrable government, to break the connection with England, the never-failing source of all our political evils, and to assert the independence of my country – these were my objects. To unite the whole people of Ireland, to abolish the memory of past dissensions, and to substitute the common name of Irishman, in place of the denominations of Protestant, Catholic and Dissenter – these were my means.’’