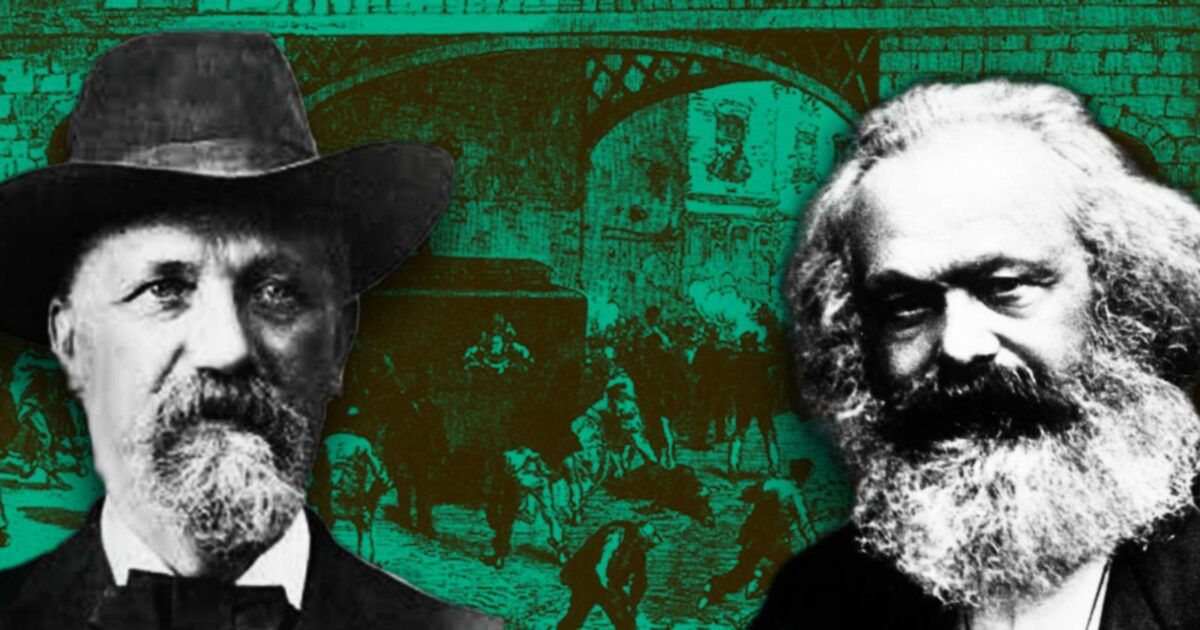

‘With the accumulation of rents in Ireland, the accumulation of the Irish in America keeps pace. The Irishman, banished by sheep and ox, re-appears on the other side of the ocean as a Fenian, and face to face with the old queen of the seas rises, threatening and more threatening, the young giant Republic’ – Karl Marx, 1867

Anti Imperialist Action mark the anniversary of the founding of the Fenian journal, the Irish People, first published on November 29, 1863. Founded in Dublin, this was a significant turning point for republicanism as it allowed the Fenian movement to increasingly influence practical politics and political discussion in their homeland. In spreading republican ideals and politics, and through fierce debate with the constitutional-nationalist papers, the Irish People did much to break down the adherence to reformist constitutionalism which had become dominant in the wake of the defeated revolutionary movement of the 1840s. As English Marxist historian T. A. Jackson wrote about the Irish People:

Demonstrating the continuity of Ireland’s revolutionary struggle, it was led by republicans who had been involved with the Young Irelander movement and the 1848 Rising. Its editors were Thomas Clarke Luby and John O’Leary (who had risen up in 1848 and had been close friends with James Fintan Lalor) alongside Charles Joseph Kickham who had contributed to the Nation, the influential paper of the Young Irelanders, led by Thomas Davis. In reference to the Nation, John O’Leary wrote, ‘we could do no more than follow in its footsteps, and by so doing we have incurred the same reward – the hatred of bigots.’

As Karl Marx recognised at the time, the monopolisation of land by the landlords following the genocidal 1840s made inevitable an agrarian-socialist tendency within Ireland’s republican movement as it was, in Marx’s words, ‘a lower orders movement’. And indeed the ideals of socialism resound throughout the articles of the journal, a reflection of the influence not only of the likes of James Fintan Lalor but also the international republican, socialist and communist movements with which some of the Fenian leaders had come into contact in France, England and elsewhere. The Fenian movement was closely tied with and supported by the International Working Men’s Association, led by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. The emancipatory ideals of these republicans, relevant long after they were written, are best expressed in the pages of the Irish People:

‘The overthrow of tyranny has always been the work of the people. It is by their combined and determined efforts that rulers are made and unmade.’

‘By force of arms Ireland was wrested from her rightful owners, the Irish people. By no other means will she ever be restored.’

‘Every man has one simple object to accomplish. It is to rid the land of robbers… which will be an inheritance worth a free man’s while to bequeath to his children, and worth the children’s while to enjoy in a nation which bows to no power under heaven.’

At the trials of the Fenian leaders (Luby, O’Leary, Kickham and O’Donovan Rossa) the primary evidence for their guilt (of preparing for an armed uprising) was drawn from the Irish People, including the above sentiments.

Nearly forty years later Russian revolutionary Vladimir Lenin, in his article Where to Begin?(https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1901/may/04.htm), would sum up the importance of a revolutionary newspaper to a revolutionary movement:

‘A newspaper is not only a collective propagandist and a collective agitator, it is also a collective organiser… it may be likened to the scaffolding round a building under construction, which marks the contours of the structure and facilitates communication between the builders, enabling them to distribute the work and to view the common results achieved by their organised labour… This network of agents will form the skeleton of precisely the kind of organisation we need’.

This is exactly what the Irish People helped to develop, building an international network of militant and radical Irish republicans who lay the groundwork for republican struggle both in their own day and in the future. When the old Fenian John Devoy, a leading figure in the 1860s, sent Thomas Clarke to Dublin in 1907 to reorganise the movement at home he took perhaps the most important step in assuring a rising would come together. As Liam Mellows, leader of the Galway IRA in 1916, wrote shortly after the Easter Rising:

‘were it not for Tom Clarke there would not have been an Easter Week… Clarke… viewed with the perspective of time, will be regarded as the father of the Rebellion, for it was he who, after serving nearly sixteen long years in English prisons, continued the work of the Fenians and laid the foundations on which the others built.’

As the Young Irelander movement of the 1840s lay the groundwork for the Fenian movement of the 1860s, in turn the Fenians lay the groundwork for the republican movement of the 1910s and ‘20s, from which emerged, among those who stayed true to the Republic, all revolutionary struggles in our country which have followed. To draw once more on the words of the brilliant Liam Mellows:

‘The [Easter] Rebellion was not caused, as some maintain, by Carsonism or by the strikes in Dublin… or the various acts of repression since the war, but was the direct outcome of the Fenian movement, which was inspired by ’48 and which in turn drew its inspiration from the United Irishmen of 1798, thus preserving an unbroken chain of successive efforts to throw off the English yoke.’

For all this a debt is owed to those who struggled and sacrificed for the Irish People. We recognise and uphold the worthy role it played for the cause of the Republic. Today there is much that could yet be learned from its pages and its history, both in regards to ideology and practical politics.